To paraphrase a wise man, “Small, weak, and injured is no way to go through life.” But if you design your workouts around the wrong exercises, that’s exactly how you’ll end up – unmuscular, weak and prone to chronic injuries.

Proper exercise selection can be tough. There are countless lifts to choose from and most of them have several variations. Fortunately, there are some objective criteria you can use to choose between similar exercises – like figuring out why an overhead extension is better for triceps than a pressdown.

This is only a partial list of criteria, but they apply to the vast majority of movements. Let’s take a look at exactly what these principles cover and how to apply them to several basic exercises.

Note: I’ve looked at each of the following factors individually, overlooking the other criteria. A full exercise assessment will include a blend of all 7 factors.

1. The Limit Factor

An exercise is most effective for a body part if that body part is a limiting factor in the execution of the movement.

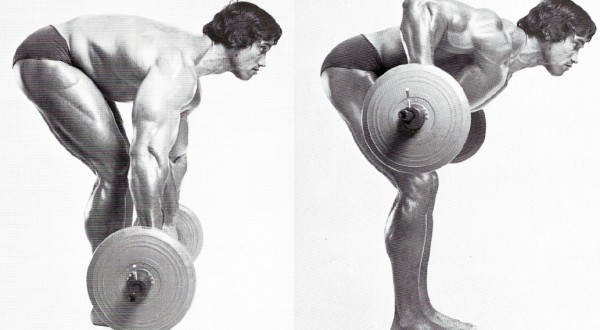

If your grip is always the first thing to give out when performing deadlifts, your posterior chain will remain understimulated. Picture courtesy of the bioneer.

If your grip is always the first thing to give out when performing deadlifts, your posterior chain will remain understimulated. This makes deadlifts a poor choice for training your lower body. Likewise, your lower chest and the long head of your triceps activate during a pull-up, but they’ll never be the movement’s limiting factor. Therefore, pull-ups are not an effective exercise for those muscles.

This criterion removes almost all unstable exercises from a bodybuilder’s exercise menu. Standing on an unstable surface will make your balance or, at best, the muscles in your feet the limiting factor in the exercise.

This principle also applies to unstable objects such as weights. For example, single-arm barbell overhead presses suck for shoulder training. Why? Because your forearms and rotator cuff stabilizers will give out long before your delts get a chance to do enough work.

2. Compoundedness

For all body parts, a compound exercise is superior to more isolated exercises.

This isn’t revolutionary. If you can train three muscles at once, why train them separately?

Compound exercises are more than the sum of their isolation exercise parts. This means the guy with the bigger bench press will always be more impressive than the guy focusing on flys and skull crushers.

Compound exercises also spread their force across several joints, which keeps joints healthy and strong. Besides, they’re a more natural way to move your body and they meet the other exercise criteria better than isolation exercises alone.

For all body parts, a compound exercise is superior to more isolated exercises.

That’s not to say isolation exercises are useless. They have their place, but they can never rival compound exercises when it comes to getting big or strong. You can certainly include curls in your program, but only if you’re also doing compound pulling exercises.

And yet – remember the note we started with? A compound exercise is superior to isolated exercises, provided it fulfills the other criteria for said body parts.

That means chin-ups are better than the combo of barbell curls and straight-arm pulldowns because they train the lats and biceps in a way that meets all other criteria. If you’re looking for efficiency, chin-ups will win every time.

For similar reasons, bench presses don’t work triceps as well as overhead extensions. Standard bench presses don’t allow for a full range of motion and they leave the long head of the tricep understimulated. As such, you can’t compare overhead extensions and bench presses using the compoundedness criterion. They’re just different, like comparing a hammer and a screwdriver. Both are good tools, but they can’t do each other’s job well.

3. Range of Motion

The more an exercise moves joints through their full range of motion, the better it is.

Time and time again, studies show that lifting with a full range of motion (ROM) is superior for building strength and mobility.

One reason is that increasing the ROM also increases the compoundedness of an exercise. For example, partial squats train the quads and spinal erectors, but full squats use the whole posterior chain. Training with ROM is also easier on your nervous system and joints because you can use lighter loads.

The more an exercise moves joints through their full range of motion, the better it is. Picture courtesy of buffalo barbell.

Wait, what? Using less weight creates a better exercise? Yes. If maximum weight was all that mattered, everybody would only do isometric or eccentric exercises and they’d outgrow clothes faster than the Hulk. But that’s clearly not the case.

We all know that the bar should touch the chest when we bench press and quarter squats are for frat kids between sets of curls, but few realize that a full ROM is ideal for all exercises.

That means that during most pulling or pushing exercises, whatever you’re gripping (bar, dumbbell, cable handle) should touch your body at some point. That includes pull-ups, rows and overhead presses.

The ROM principle also means that the best grip for most exercises is near shoulder width. Because of the way our bodies are built, a shoulder width stance offers the greatest ROM, especially for pushing and pulling movement patterns. The only exception is if your hands interfere with the ROM, like in a military press where your hands have to move slightly outward.

In short, neglecting an exercise’s ROM demands a damn good reason. And for the record, “a shorter ROM lets me go heavier, and that gives me an ego-boner” is a damn silly reason.

4. Tissue Stress Distribution

The more an exercise applies stress to its targeted areas, the better the exercise.

Targeted exercises should focus on muscles first and peripheral tissues, like tendons, second. Bone density, tendon strength and cardiovascular health naturally increase with high-intensity compound exercises, which means you can put all your energy towards building strength. (See my previous Muscle Specific Hypertrophy articles for more on how to maximally stimulate individual muscles.)

The classic example is to compare a push-up to a flat dumbbell press. In the first, you’re moving (closed chain). In the second, the object is moving (open chain). Image courtesy of the if life

This criterion is best applied to single exercises, but you can also make some generalizations.

The following are sub-criteria of this principle:

- Your body isn’t built to push against things that are behind you – it causes unnatural and unnecessary shoulder stress. As a result, you should exclude exercises such as dips, behind-the-neck presses and behind-the-body side or front raises.

- The “core” is built to stabilize the spine, not move it. Spinal movement, especially flexion, is unnecessary for bodybuilders. Never round your back. Instead, keep it flat or arched. Natural, anatomical position is almost always the best for force transfer and core activation. It also helps reduce peripheral tissue stress, such as spinal shearing forces.

- The more an exercise forces your body into a specific movement pattern, the worse it is. So… dumbbells are more favorable than barbells which are more favorable than machines. Free weights generally have very acceptable tissue stress distribution, while machines almost never do.

- Closed kinetic chain exercises are superior to open kinetic chain exercises.

When you apply force to an object, either you move or that object will move. If you move, the exercise’s kinetic chain is closed. If the object moves, the kinetic chain is open. The classic example is to compare a push-up to a flat dumbbell press. In the first, you’re moving (closed chain). In the second, the object is moving (open chain).

Closed chain exercises allow your body to determine which joints move and how much, which reduces joint stress and lets the muscles do the work.

This finding has been replicated many times and is hugely underrated. The fact is, closed chain exercises are better for your joints and your muscles. This is why squats are superior to leg presses and pull-ups are better than pulldowns. It’s also why rows and bench or overhead pressing exercises aren’t ideal.

5. Dynamic Contraction

Exercises that use eccentric and concentric movements are superior to those that are only isometric, concentric or eccentric.

Concentric movements work best when immediately preceded by the eccentric phase of the movement. That’s how you naturally jump, kick in doors, and throw heavy objects at people doing curls in the squat rack.

Long-term studies that measure increases in cross-sectional area (muscle mass) consistently support this concept. Contrary to popular belief, the hierarchy of muscle building is:

- eccentric-concentric contractions

- isometric contractions

- concentric contractions

- eccentric contractions

This hierarchy reinforces the same theme repeated in several principles so far. “Natural” movements, or those dictated by the structure of your body, are superior.

Concentric movements work best when immediately preceded by the eccentric phase of the movement. That’s how you naturally jump, kick in doors, and throw heavy objects at people doing curls in the squat rack.

Oh, and it’s the most effective way to do most exercises, too.

6. Strength Curve = Resistance Curve

The closer an exercise’s resistance curve resembles a healthy strength curve, the better the exercise.

If you routinely fail to lock out your deadlifts, there’s no problem with the deadlift itself. It’s a problem within your structural balance. Image courtesy of muscle for life.

If an exercise’s strength and resistance curves don’t match, some muscles will remain understimulated. You know how you usually fail exercises at the same point? For a healthy trainee, that point shouldn’t exist. Failure should only occur when your less developed muscles can no longer apply enough force.

Matching strength and resistance curves allow you to avoid this by engaging all the muscles used in the lift in a balanced manner.

Note the explicit mention of a healthy trainee.

If you routinely fail to lock out your deadlifts, there’s no problem with the deadlift itself. It’s a problem within your structural balance. You most likely have weak glutes, which create a sticking point somewhere in the movement.

Exercises that meet this criterion balance you out because your weakest muscles get more attention than the others. In the case of deadlifts, the exercise’s point of failure depends on the condition of your glutes. Strong glutes, strong deadlifts.

Resistance Curves

The resistance curve for many exercises is flat, meaning there’s a constant resistance.

For example, muscle resistance is lowest at the bottom of a dumbbell curl, but maxes out at 90-degrees flexion (the midpoint). Image courtesy of pixshark.

The weights don’t increase or decrease and gravitational acceleration is constant, unless you’re training on a space station in orbit. Exercises that require the weight to move vertically (directly opposed to gravity’s pull) also have a constant resistance curve.

Resistance curves for “circular” exercises (think leg extensions and barbell curls) hit their maxima when the target area is horizontal and their minima when the area is vertical.

For example, muscle resistance is lowest at the bottom of a dumbbell curl, but maxes out at 90-degrees flexion (the midpoint). That may seem easy enough, but to determine the exact resistance curve for other movements, you may need a solid understanding of physics.

Strength Curves

How do you determine your strength curve?

Well, besides noting where you’re strongest and where you fail during an exercise, it helps to think of a muscle’s length-tension relationship. We know muscles are strongest in their natural anatomical position (think military posture) or when in a moderately stretched position, but we also need to know when they hit peak resistance in a particular exercise.

For pushing exercises, the resistance is generally greatest at the beginning of or halfway through the concentric part of the movement. This is why, in the case of the overhead press, bench press, or squat, you’re more likely to fail at the bottom of the rep or before reaching the halfway point.

This is why, in the case of the overhead press, bench press, or squat, you’re more likely to fail at the bottom of the rep or before reaching the halfway point. Image courtesy of muscle mag.

For pulling exercises, the resistance is generally greatest at the end of the concentric portion. This is why, for example, so many people find it nearly impossible to actually touch their chest to the bar when doing pull-ups. (Note: This isn’t giving you a cop-out for such an inability. If you can’t touch your chest, you’re weak or fat. Either build some mid- and lower-trap strength or cut some fat, pudgy.)

Sizing It All Up

So how do we match our strength curve to the exercise’s resistance curve?

Many people take the easy way out and simply avoid the hard parts of exercises. The trouble with their “solution” is that it clearly violates the ROM principle. It also certifies them as nitwits who probably text their own mother “Hpy bday 2 u” instead of mailing her a birthday card because it’s easier.

A real solution would be to use accommodating resistance like chains or bands. Several longitudinal studies have found that adding chains or bands to the bench press increases strength and muscle gains.

While it’s also true that some studies have found no differences, that’s likely because it can be difficult to know how much chain or band to use. If you apply too much added resistance, you negate all the benefits. If you apply too little, you can still squeak out some benefit but it’ll be sub-optimal. Just like Goldilocks, the right amount will be somewhere in the middle, where the resistance curve equals the strength curve.

Although most exercises can benefit from this technique, it’s not going to be practical in all cases. Some movements are so involved that you’d be in a constant process of fine-tuning just to find the right resistance.

If this is the case, or even if chains or bands just aren’t available at your gym, you can instead rely on your natural stretch reflex. When a muscle lengthens, the strength of subsequent contractions increase. Popular theory says that this strengthening is due to elastic energy from the stretched muscle, as occurs when you stretch an elastic band – the farther you stretch it, the harder it pulls.

A real solution would be to use accommodating resistance like chains or bands. Image courtesy of auspeakthetruth.

Though that theory is partially correct, comparing stretched muscles to elastic bands is too simplistic. In fact, the stretch reflex is largely a neural process. Muscle lengthening increases motor neuron activity, which is what tells your muscles to do the work.

If it really were just a process of elasticity, it would occur even without an active contraction afterwards. You can easily test this. Dive-bomb down during a squat and see how far you “effortlessly” bounce back up. (Okay, on second thought… just imagine dive-bombing down on a squat. Your patellar tendons will thank you.)

The stretch reflex is still a good way to accommodate an exercise’s resistance curve, especially for pushing exercises. It can also be used for some pulling exercises where strategic momentum can help you to overcome weak points in the movement.

Face pulls, for example, have a strength curve that decreases as you move along the concentric part of the movement. This makes the exercise uselessly-easy at the start and increasingly difficult as the bar approaches your face.

This is where momentum comes in. Don’t just pull on the handle. Heave it and make sure it practically brushes your eyebrows at the end. But remember, you need to be structurally balanced and injury-free before using any type of strategic momentum. If you aren’t, you’ll just exacerbate your imbalances by allowing the underdeveloped muscles to avoid training stress.

7. Microloadability

The more precisely an exercise’s resistance can be determined, the better the exercise.

The best mass-building exercises work with both high absolute loads and small incremental loads. In other words, we can increase the max weights used, but we can also take baby steps towards those maxes.

Absolute, or maximum, load is generally a limiting factor in bodyweight exercises. For example, handstand push-ups have a better kinetic chain than overhead presses (closed vs. open), but their absolute loading capacity is far worse. Once you’re in beast-mode and doing handstand push-ups for reps, how do you add resistance? Yeah, exactly.

The ideal incremental load should be measured in a percentage of the working weight, not a strict 5 or 10 pounds. Image courtesy of black iron strength.

Incremental loading is also a limiting factor for many exercises. Machines have fixed weight increments and most gyms have dumbbells that only increase five pounds at a time. Even barbell exercises can only use the gym’s smallest plates multiplied by two (lopsided bars are a bad idea, no matter how “small” the imbalance is).

While beginners and intermediates may be able to progress with such rigid increases, the ideal incremental load should be measured in a percentage of the working weight, not a strict 5 or 10 pounds.

Five pounds may a good incremental increase for barbell rows, but it can be inefficient and excessive for shoulder isolation work. This is why small magnetic add-ons, like PlateMates, can be so beneficial. If you have them, be sure to use them. If you don’t have them, put them at the top of your list of “Lifting Toys I Gotta Buy”.

Practical Application of the 7 Principles

Now that you’ve made it through the lesson, it’s time to see the rules at work. Let’s apply the exercise selection criteria to a few basic movements.

1. We’re hitting triceps today. Should we do two-arm kickbacks, rope pushdowns or standing overhead extensions with a rope?

Well, they’re all dynamic contractions with triceps as the limiting factor. They also have similar tissue stress distributions, although ropes are generally easier on the joints.

The microloadability depends on your gym’s equipment, specifically the dumbbells and weight stacks. Kickbacks require such small weights that incremental loading is a pain (unless you’ve already ordered those PlateMates).

Overhead extensions are the most compound because the overhead position puts you in full shoulder flexion and allows the long head of the triceps to participate fully, which is not the case with the other two exercises.

The microloadability depends on your gym’s equipment, specifically the dumbbells and weight stacks. Image courtesy of imagesoup.

All three exercises allow a full ROM, but overhead extensions have the benefit of a resistance curve that better approximates the human strength curve. Kickbacks and pushdowns have very little resistance at the stretched position.

Overhead extensions also have an increasing resistance curve along the eccentric movement, which allows you to use the stretch reflex.

Therefore… drum roll please… overhead extensions are the best exercise of the three.

2. Everybody says deadlifts are magical mass-builders, but how do they score using the criteria?

I know I’m going to upset a lot of people with this, but deadlifts are not a good tool for increasing mass.

They don’t use dynamic contractions, which is a huge downside. Deadlifts also put the legs through a limited ROM that’s arbitrarily determined by the radius of a standard 45-pound plate.

These issues can be partially resolved by not resetting between reps, using a very wide grip, or using an extended ROM (from a deficit or with smaller plates). Even then, the exercise doesn’t satisfy the limit factor principle because secondary muscles like your grip or erector spinae are most likely to give out first.

However, that’s not to say that all deadlift variations are bad for bodybuilders. Romanian deadlifts, for example, are still a great exercise. Image courtesy of muscle mag.

Deadlifts aren’t even ideal for those muscle groups because they’re slow-twitch dominant and need much higher volume for optimal growth. Working deadlifts at such a high volume will leave your nervous system fried and extra crispy, like everyone’s favorite breakfast side dish.

However, that’s not to say that all deadlift variations are bad for bodybuilders. Romanian deadlifts, for example, are still a great exercise.

Final Words

By now, you’ve hopefully absorbed enough to start making better, more deliberate exercise choices.

Just like any other element of training, optimal exercise selection should be systematic and based on objective criteria. It can be tempting to do the convenient and comfortable exercises, or the ones that make you feel like a badass. Those feelings are deceitful and short-lived. Smart training means the physique you build will be lasting, visible proof of your dedication to the iron.

I always have to remind people, “Do you want to look good for the one hour you’re inside the gym or for the 23 hours you’re outside of it?”

So put the time into designing the best program, do the hard work and earn the results.

About the Author

Online physique coach, fitness model and scientific author, Menno Henselmans helps serious trainees attain their ideal physique using his Bayesian Bodybuilding methods. Follow him on Facebook or Twitter and check out his website for more free articles.

Online physique coach, fitness model and scientific author, Menno Henselmans helps serious trainees attain their ideal physique using his Bayesian Bodybuilding methods. Follow him on Facebook or Twitter and check out his website for more free articles.